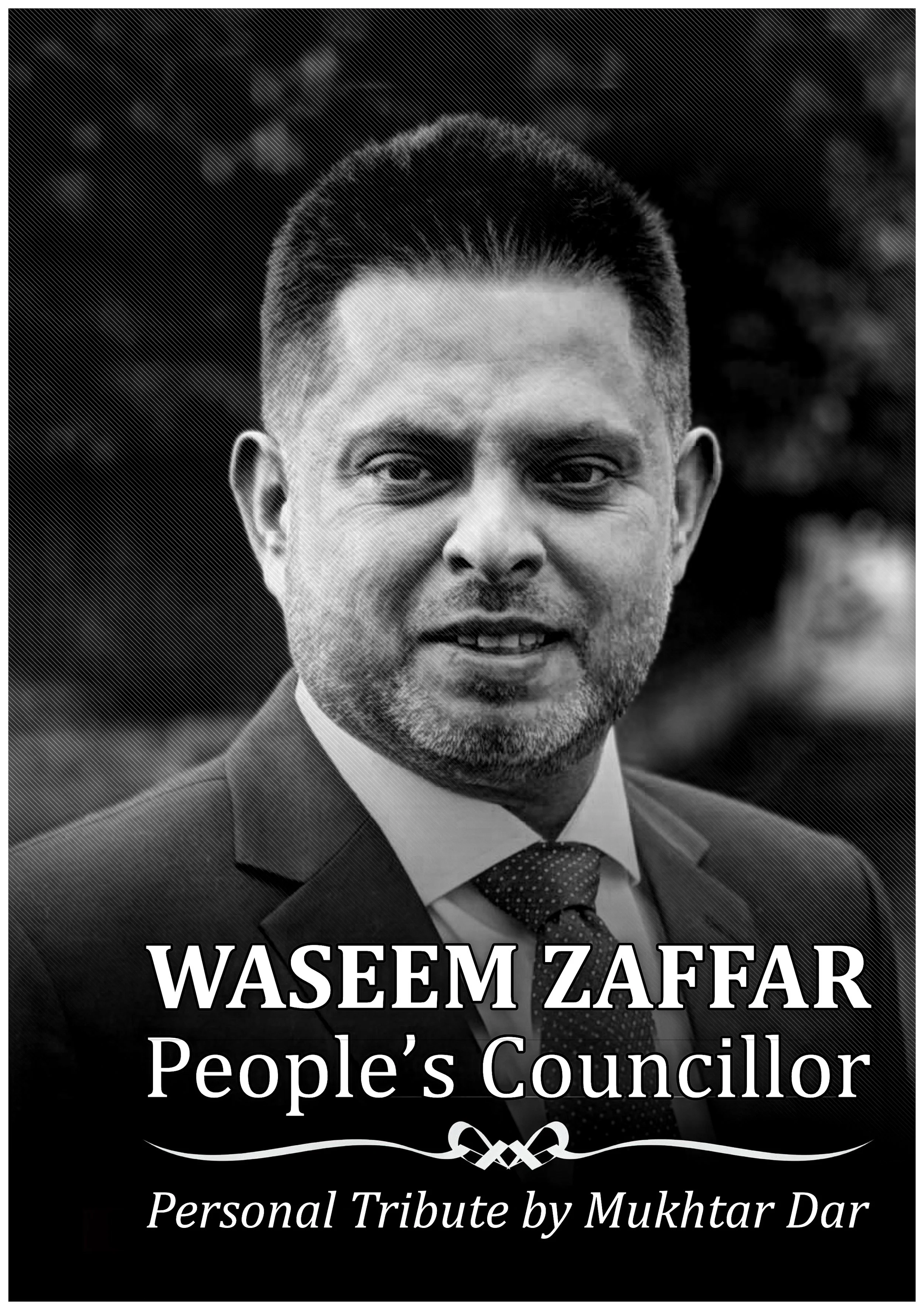

Waseem Zaffar: From Lozells to Birmingham — A People’s Councillor

There are departures that do more than remove a person from view; they rearrange the emotional architecture of a city. Waseem’s passing was one such loss — sudden, disorientating, and made all the heavier by the knowledge that he was only forty-four, an age when most public lives are only just finding their full voice. His death did not merely take a councillor from Birmingham; it removed a presence from its streets, a familiar figure from its doorsteps, and a trusted ear from its communities.

The circumstances of his final days carry a poignancy that words struggle to contain. He had travelled to Azad Kashmir to attend the funeral of a beloved uncle, standing in grief with folded hands and tearful eyes, unaware that within hours his own life would be claimed. The image that remains is not political or ceremonial, but profoundly human — a man mourning family, and then a family mourning the man. Later, his young son would stand in the same posture, grief echoing across generations. Even those who seem tireless and ever-present are, in the end, as fragile as the rest of us.

Yet Waseem was never defined by tragedy; he was defined by love — particularly for his family. A devoted husband to Ayesha, a father to three young boys, and eagerly awaiting the birth of a fourth, he spoke of family not as an accessory to his career, but as its anchor. Amid the relentless tempo of public life, he remained present in the ordinary rituals that matter most: school runs, shared meals, weekend football matches, and the quiet pride of watching his children grow. Walking beside his eldest son, Mikaeel, to Aston Villa games was more than leisure; it was inheritance, tradition, and belonging woven into a single gesture.

Beyond the home, he belonged to an even larger family — the people he served.

To call Waseem merely a councillor is to understate the essence of who he was. He was, in the truest sense, a people’s councillor. Elected in 2011 to represent Lozells, he went on to hold senior cabinet responsibilities on Birmingham City Council, including transport, environment, climate change, highways, equalities, and social justice. He became a leading figure behind Birmingham’s Clean Air Zone — a policy rooted not in abstract environmentalism, but in lived experience and concern for public health. He championed safer routes for schoolchildren, housing standards, youth engagement, and neighbourhood wellbeing — the kinds of issues that rarely trend online, but quietly shape the texture of everyday life.

What distinguished him was not merely the breadth of his portfolio, but the manner in which he carried it. He did not govern from a distance. He was on the streets, knocking on doors, listening without hurry, attending surgeries, answering difficult questions without evasion. He did not hide behind press statements or curated photographs. He showed up — early, late, and often unannounced — in community centres, youth clubs, mosques, gurdwaras, mandirs, churches, and Rastafarian gatherings alike, because he understood that representation is not a title; it is a relationship.

Perhaps what made this even more striking was his age and authenticity. Waseem was possibly the youngest councillor I knew personally, and those who know me will recognise that I tend to keep politicians at arm’s length. Too often public life attracts those chasing optics rather than outcomes — elevated by clan loyalties or reactionary biradari arithmetic, fluent in slogans yet thin on substance. Waseem was the rare exception. At forty-four, he possessed clarity of thought, humility of manner, and an accessibility that many twice his age never acquire. He could articulate ideas coherently in both English and his mother tongue Pahari Mirpuri, but more importantly, he could listen coherently — and listening is the rarer skill.

He was a product of Lozells in the fullest sense — not merely raised there, but shaped by its diversity, struggles, and resilience. Lozells is one of Birmingham’s most deprived yet culturally vibrant wards, marked by both social unrest and extraordinary community strength. Waseem embodied that duality. He carried with him the multicultural fabric of his neighbourhood: Kashmiris, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Indians, African Caribbeans, and white English families all found in him someone approachable, recognisable, and unguarded.

Tributes that flooded social media were not confined to officials or party colleagues; they came from ordinary Brummies whose lives he had touched in small but meaningful ways. He did not merely visit communities — he belonged to them.

That belonging was reflected powerfully in the voices of those who grew up with him and later became pioneers in their own right — people from entirely different ethnic and cultural backgrounds who nonetheless shared the same memory of his loyalty and encouragement. Aftab Rehman, Ammo Talwar, Jesse Gerald, Professor Carl Chinn, Abid Iqbal, Lloyd Blake, Shaffaq Hussain, Ayoub Khan, Mona Qazi, Camille Ade-John, amongst many others, spoke not from political obligation, but from personal history. Their tributes were less about office and more about friendship, less about policy and more about presence. In their words, one could see the geography of Lozells and wider Birmingham itself: diverse, layered, and bound together not by uniformity but by familiarity.

He did not evade criticism either. He absorbed it, confronted it, and, where necessary, defended his decisions with evidence rather than bluster. I first encountered Waseem during my time as artistic director at the Drum Arts Centre in Aston, a period filled with its own complexities. In that environment, he became someone I could quietly turn to for perspective when situations or personalities became murky. I trusted his judgement. He had a youthful face, almost disarming, yet a steadiness beneath it that communities across North Birmingham recognised and relied upon.

One of my most enduring memories of him speaking truth to power came during our work on the Simmer Down Festival. Months after a successful event, police representatives alleged their officers had come under attack from youths pelting bricks and bottles as the festival closed in Handsworth Park. Waseem convened a meeting with senior officers at Handsworth Police Station and calmly asked the questions others hesitated to raise: Why had this not been recorded at the Safety Advisory meeting? Why had no security teams witnessed it? Where was the CCTV footage from adjacent cameras? Why no mobile recordings? Where was the official police log that had apparently gone missing? He chaired the meeting with composure and insistence on facts rather than theatrics. An apology from the highest echelons followed. It was not a victory for ego, but for fairness and accountability.

I did not always agree with him politically — and that truth deserves to stand alongside the praise. We differed on a number of issues, including the right of the people of Kashmir to self-determination, even independence from both India and Pakistan should they choose. Yet disagreement never turned into distrust; if anything, it deepened mutual respect. Indeed, as an example of that trust, despite our differing views on Kashmir I still asked him to chair the post-screening panel discussion of No Fathers in Kashmir at the Midlands Arts Centre. He was often the person I turned to for clarity when navigating the more uncertain edges of public life. That same trust is why we later invited him onto the Simmer Down Festival board.

Beyond politics, Waseem championed cultural celebration as a means of community building. He played a leading role in Birmingham Heritage Week, chairing the steering group and guiding a city-wide celebration of collective histories and shared cultural inheritance. Through tours, exhibitions, talks, and community events, he brought people together and reinforced his lifelong commitment to fostering understanding, connection, and civic pride across Birmingham.

He carried that same convening energy into the Spirit of Pakistan Festival, which he led from inception. Only he could have assembled and galvanised Kashmiri and Pakistani programmers, artists, and promoters into such a wide-ranging partnership, uniting individuals and organisations that did not always naturally occupy the same space. Working alongside him on that initiative became one of the most strategic and much-needed undertakings of my creative practice in recent years.

As part of the festival’s launch, he commissioned me to create a multi-artform narrative spectacle, WAQT: Pakistan in Motion, which explored Pakistan from the perspective of its people rather than the posture of its state. It was layered, questioning, and at times deliberately uncomfortable. Afterwards he laughed and remarked that the performance had made the Pakistani Ambassador visibly uneasy — a comment delivered not with malice, but with the quiet satisfaction of knowing art had done its job.

Around the same period, my photographic exhibition Morgah Memories opened at the BRIG Warehouse Café. We found ourselves waiting for the Pakistani Consul General, diverted en route by a well-meaning political detour for tea. I still recall Waseem’s expression — a mixture of irritation and amusement — as he balanced diplomatic protocol with grassroots reality. Moments like these revealed his rare skill: he could navigate officialdom without ever losing his footing among ordinary people. He listened when we spoke candidly and never confused rank with wisdom.

His advocacy for Palestine was longstanding, consistent, and public, even when it put him at odds with prevailing opinions within his own party. While the leadership and many in the Labour Party were complicit in the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people, Waseem stood firmly on the right side of history, supporting Palestinians and advocating for a two-state solution.

That same courage and integrity carried over into his local work. When the decision was made to ban Maccabi Tel Aviv fans from attending Aston Villa, Waseem was once again singled out, unfairly “thrown under the bus” for his role in the Safety Advisory Group. It was a classic case of political scapegoating, yet he faced the criticism with the same steadfastness he had shown throughout his career. Whether advocating on an international stage or navigating highly charged local issues, Waseem never shied away from difficult terrain. He confronted contentious decisions head-on, guided by principle rather than convenience, demonstrating a rare commitment to doing what was right, even when it invited controversy.

Away from politics, he was an avid Aston Villa supporter, a season-ticket holder who shared that passion with his sons. Football, for him, was less about sport than about belonging — a shared language that crossed class, culture, and generation.

Tributes emerged not because protocol required them, but because affection compelled them. Friends recalled his annual Nowka Bais boat-race invitations — messages sent each year with humour, optimism, and unwavering persistence, regardless of whether victory ever followed. In the BRIG newsletter and beyond, colleagues described him as a “powerhouse,” a “champion of the community,” and “part of our future.” These were not polished lines drafted for formality; they were spontaneous reflections from people who had encountered him not as a distant figurehead, but as a neighbour, an ally, and an attentive listener.

And perhaps that is where the true measure of his life resides — not in offices held, controversies weathered, or speeches delivered, but in the simple, unquantifiable truth echoed by so many: he showed up.

The lesson in the outpouring that followed his passing is a sobering one for public life. While many councillors chase higher office, polish their images, and hover where cameras gather, Waseem came from one of Birmingham’s most deprived and super-diverse wards — a place with a history of unrest, resilience, and reinvention. He was not parachuted into Lozells; he was produced by it. He believed in his constituents, and in turn they entrusted him with their respect. The vast, diverse wave of grief and tribute that rose from his village, Thub Jagir in Azad Kashmir, to Lozells and rippled across Birmingham was not orchestrated; it was organic. It revealed something increasingly rare: a public servant whose legitimacy came not from party endorsement or media exposure, but from everyday presence and earned trust.

In a political age dominated by performance, Waseem’s legacy stands as a reminder that authenticity, humility, and accessibility still resonate — and that a true people’s councillor is measured not by how high he climbed, but by how deeply he was rooted among those he served.

Rest in Power, my brother.