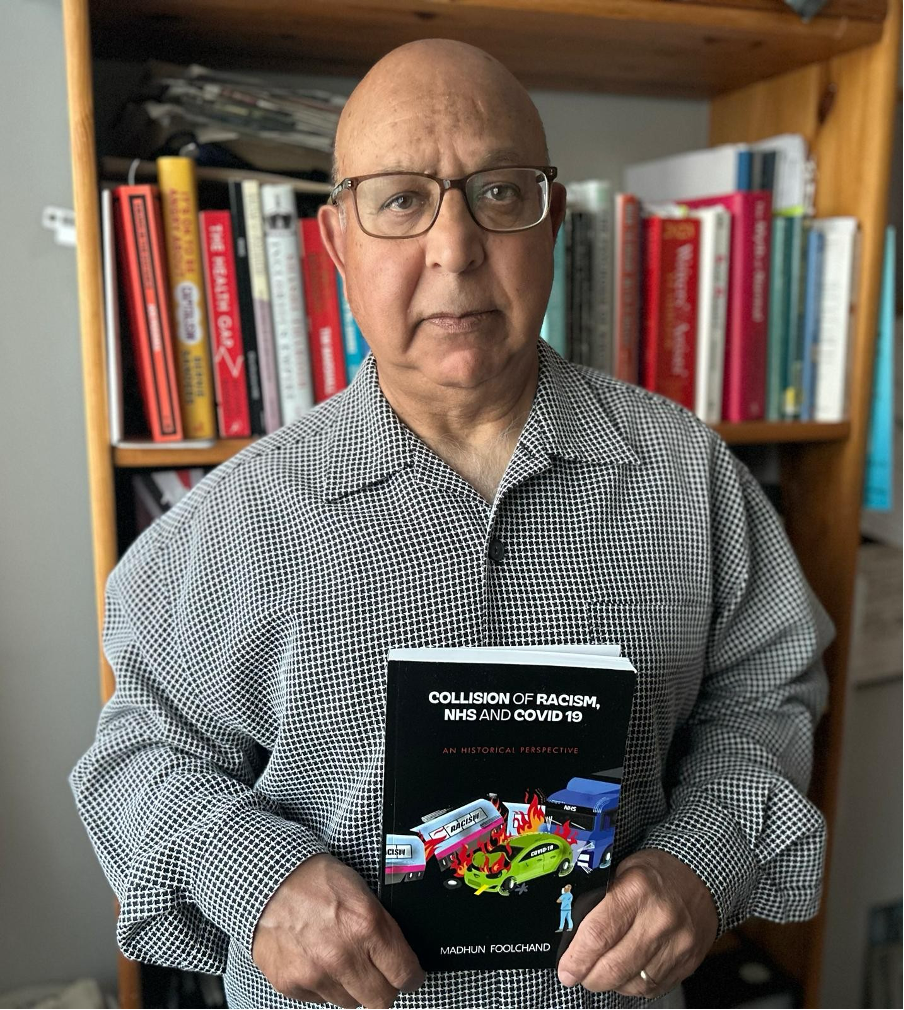

Racism, the NHS and the Truth We Avoid In conversation with Madhun Foolchand

In a thoughtful and wide-ranging conversation with BRIG, Madhun Foolchand, former nurse, lecturer and long-standing campaigner for health equity, spoke about his book, Collision of Racism, NHS and Covid-19, and the histories many of us still struggle to face.

Asked to describe what the book is really about, Foolchand was clear. The NHS, he said, does not sit apart from society. It reflects it. The racial hierarchies shaped by colonialism and white superiority were already present in British institutions long before the NHS was created, and they shaped the health service from the very start.

He traced this history back to the post-war period, pointing to the sharp contrast between how Polish migrants were welcomed and supported through the Polish Resettlement Act of 1947, and how people arriving from the Caribbean and former colonies were met with hostility and exclusion. This was despite the fact that many were British subjects who had also contributed to the war effort. These choices, he argued, tell us a great deal about who was considered welcome and who was not.

Those same patterns, he explained, showed up clearly inside the NHS itself. From its earliest years, Black and Asian doctors and nurses were systematically channelled into the least prestigious and most demanding roles — mental health hospitals, learning disability services, elderly care, and deprived inner-city GP practices, often with little chance to progress. Senior leadership, meanwhile, remained overwhelmingly white.

Covid-19 did not create these inequalities. It brought them into sharp focus. Foolchand spoke about how Black and Asian staff were more likely to be placed on the frontline, often without adequate protection. Personal protective equipment was designed around a “white face model”, leaving staff who wore head coverings, had beards, or different facial structures at greater risk. Speaking up was rarely safe. Fear of bullying, stalled careers, or visa insecurity kept many people quiet.

Foolchand was also clear that racism must be recognised as a significant determinant of health. Long before the pandemic, Black and Asian communities were already experiencing poorer outcomes in areas such as maternal health, mental health, sickle cell care and later-life provision. Covid-19 simply made existing harms harder to ignore.

So what needs to change? For Foolchand, policy on its own will never be enough. Real change requires accountability - pressure from below and responsibility at the top. It means collective action, informed challenge, better representation in leadership, and communities equipped to ask difficult, evidence-based questions.

Despite everything, he remains hopeful. His hope is rooted not in blind optimism, but in history; in the resilience of those who came before, and in the belief that progress only comes when people refuse to stay silent.

His message to NHS and government leaders is simple and direct:

“We are part of society. We pay our taxes. We deserve a better service, and you have to deliver it. Not in a piecemeal way, but systematically.”